Last weekend, I attended the Rochester Memorial Art Gallery’s Haudenosaunee Heritage Celebration Day. I was very impressed by the artists there, who practice as part of a living, growing Seneca culture. But mostly I was there for the wampum. Show me the wampum!

First, a little definition of terms. The Haudenosaunee are also known as the 6 Tribes of the Iroquois Confederacy, or the New York Iroquois. The Haudenosaunee Confederacy occupied the land that is now considered New York State, from Lake Erie to the Hudson River. The Haudenosaunee Confederacy was the most powerful group of united tribes in the Eastern US, and they laid claim to hunting grounds as far away as Illinois to the west and Virginia to the south. They also had political control over the tribes in Pennsylvania. When I was in middle school, I was taught the mnemonic device “SCOOM” to remember the names of the NY Iroquois tribes: from west to east, Seneca, Cayuga, Onondaga, Oneida, and Mohawk. The sixth tribe is the Tuscarora, who were chased out of North Carolina by White settlers and adopted by the Haudenosaunee in 1722. Rochester, NY is on land once owned by the Seneca tribe, so our Haudenosaunee Heritage Celebration Day was mostly a celebration of Seneca culture.

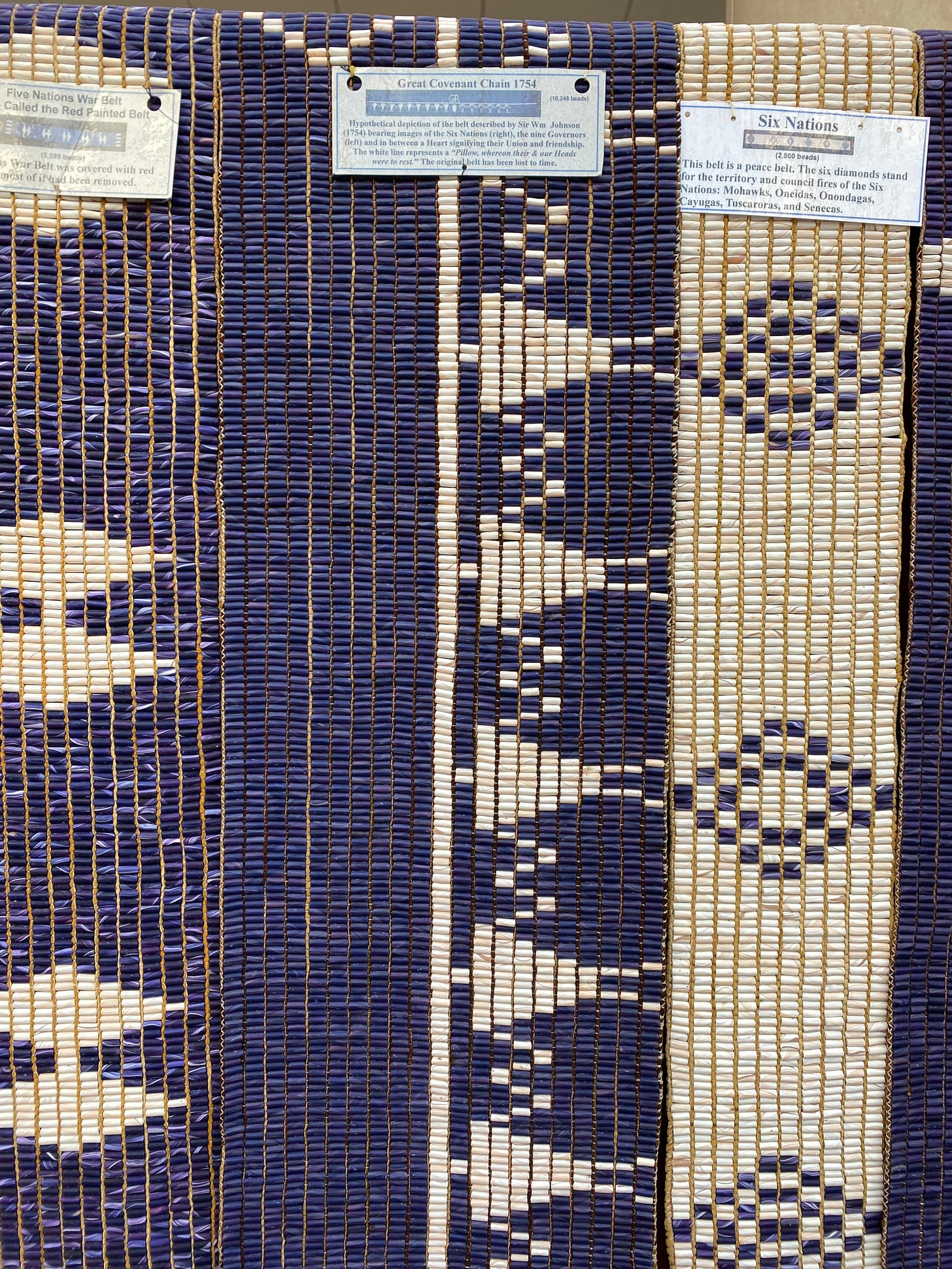

Wampum had many uses for the Haudenosaunee people: currency, diplomacy, communication, expressing condolences, developing trade and tribute networks, denoting new public policies and alliances, and adding to the historical record. Wampum is made from clam shells and whelk shells, mostly manufactured by Long Island tribes and sent to the Haudenosaunee as tribute or as trade.

Research Rabbit Hole Warning: I spent some productive time trying to figure out what the Haudenosaunee had to trade that Long Island tribes, such as the Shinnecock, didn’t have. I read that they traded tobacco, but how did the Iroquois, who live in one of the world's Lake Effect Snow Zones, get tobacco? It turns out that Western New York and Northern Pennsylvania were growing tobacco up until the 1930s! Also, in New York, it is legal to grow your own tobacco for personal use.

During the French and Indian War, the Haudenosaunee did not have a written language. However, they used hieroglyphs and other symbols in their wampum belts, which were sent from tribe to tribe to communicate the political news, like diplomatic dispatches. I was very lucky in that the museum had reproductions of the major French and Indian War belts, although I suppose I shouldn’t have been surprised, as the mid-1700s would have been the height of Seneca power. So let’s take a look!

The 1754 belt was the result of a Congress of 7 colonies: New York, New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Connecticut, Rhode Island, Maryland, and Pennsylvania. The colonies of Virginia and North Carolina sent messages, resulting in the 9 colonies represented on the belt. Sir William Johnson, Crown Superintendent for Indian Affairs in the Northern Colonies, visited the Haudenosaunee in Onondaga with offerings of peace and tribute from the 9 colonies. Johnson told the Governors of the colonies that “mere messages” to the Iroquois Confederacy were “valueless unless attended or confirmed by a string or belt of wampum, which they look upon as we our letters, or rather bonds.”

The Fort Niagara treaty belt is the last gasp of the French and Indian War, when Indians were still fighting but the French had practically given up. The Haudenosaunee Confederacy was an English ally throughout the war, but in this last stage, the Senecas wanted to withdraw from the alliance. The English had promised to abandon forts on the Mohawk River when the French left, but the French left and I’ll bet you can guess what the English didn’t do. In 1764, the Senecas admitted defeat and surrendered Fort Niagara at Niagara Falls to the English, delivering up “all prisoners, deserters, Frenchmen, and Negroes.”

Today, the the complex patterns of a showcase wampum belt are drawn up on a computer. If you’re familiar with weaving, the pattern for a wampum belt will look familiar to you, as will the wampum belt on the loom.

Weaving has always been women’s work. Weaving is tedious and repetitive enough to allow for child care at the same time, and it doesn’t involve large animals who could be dangerous to children underfoot. Additionally, the amount of time it takes to weave cloth from thread is mind boggling. For most of human history, girls and women had to spin, weave, sew, and launder for almost all their waking hours. Just as Viking women devoted years of their lives to making sails, and European women documented the Norman Conquest and other glorious victories in tapestries, Iroquois women wove wampum belts to celebrate victory and promote peace.

What I find fascinating is that the fabric arts have a special role in the relationships among White settler groups and Native tribes. An Englishwoman settled in Central New York in the 1750s was freed from weaving in a completely new way, due to commerce from India and the first mass produced goods. A Haudenosaunee woman in the 1750s was also approaching clothes making in a completely new way, due to the influx of European trade goods such as wool and metal needles. Women were also driving these economies, as Native tribes traded beaver pelts and deerskin prepared by women for woolen cloth to keep them warm in the winter.

Therefore, I can’t think of anything more emblematic of the French and Indian War than a wampum belt. Here is an ancient art, influenced by newcomers, that tells the story of these struggles. It’s up to us to learn to read the symbols.

References:

Pound, A. Lake Ontario: The American Lake Series. The Bobbs-Merrill Co., 1945.

Beauchamp, W. A History of the New York Iroquois. Ira J. Friedman, 1968.

Wayland Barber, E. Women’s Work: The First 20,000 Years. W. W. Norton and Co., 1994.

For more about Seneca music:

https://www.senecasongs.earth/

Visit Bill Crouse on YouTube to listen:

For more about Seneca wampum art:

https://oneida-nsn.gov/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/WAMPUM-OUR-HISTORICAL-RECORD-9.13.pdf

A most interesting piece! I certainly had no idea that New York was a site for tobacco production.

Fascinating indeed